Navigating Rates

Should investors believe in a soft landing?

A “soft landing” scenario that avoids recession is now the consensus call for the US economy. What do previous recession-resistant rate cycles tell us about the likelihood of a favourable outcome this time around?

Spoiler: a soft landing looks difficult to engineer.

Key takeaways

- Hopes of a soft landing in the US have been fueled by robust economic data, declining inflation and the strong performance of risk assets in the first half of the year.

- Previous soft landings all featured a swift easing of monetary policy by the Fed, as well as improvements in supply-side factors such as productivity and labour supply.

- Compared to these previous episodes, today’s economic environment looks far more challenging.

- We remain skeptical that the Fed can curb inflation without a more substantial weakening of the labour market, which has historically been a trigger for recession in the US.

A soft landing – avoiding recession despite a significant tightening of monetary policy – is notoriously difficult for central banks to achieve. In the US, we identify only three instances (1966, 1984 and 1995) since the 1960s where interest rates have been increased by 300bp or more without a subsequent recession in at least the following three years.

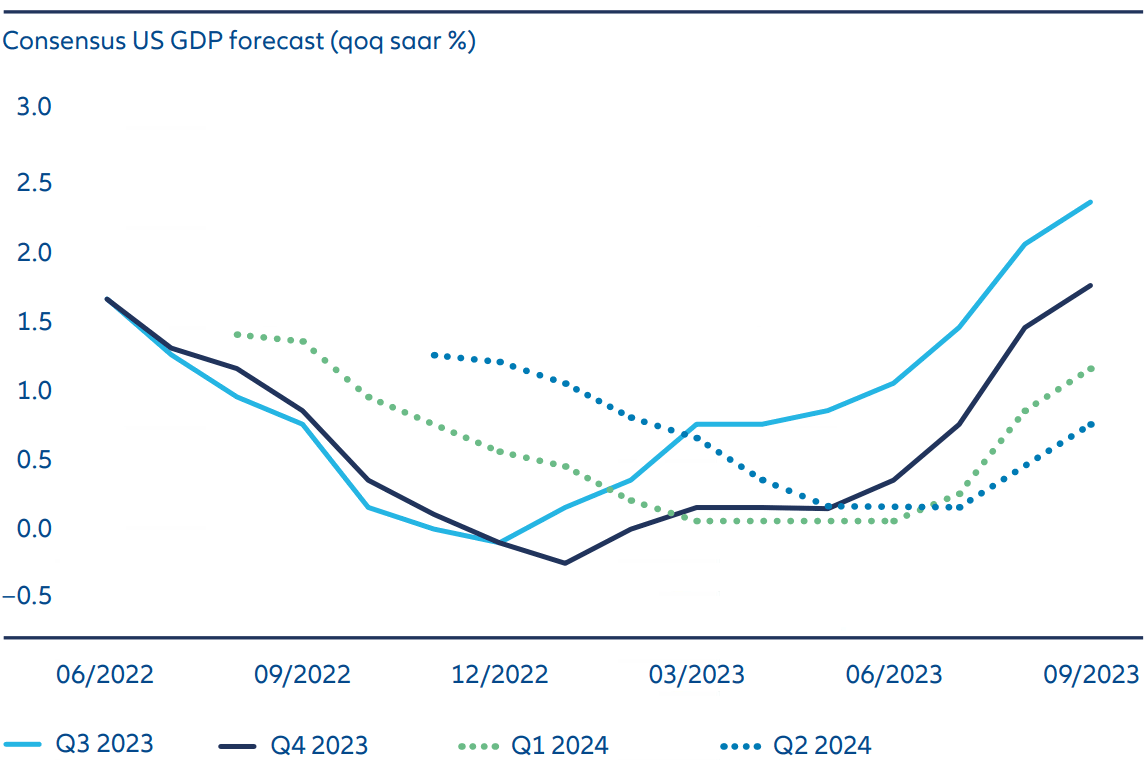

But despite this track record, and despite the US Federal Reserve’s most aggressive rate hike cycle in four decades, investors, economists and Fed officials themselves have become increasingly optimistic of adding 2023 to the list (see Exhibit 1).

Exhibit 1: Consensus US GDP forecasts have picked up strongly

Source: AllianzGI Global Economics & Strategy, Bloomberg, data as at 30 September 2023

It is therefore valuable to examine past episodes and compare them both with past recessions and today’s economic environment.

What does a soft landing economy look like?

Of course, each of the episodes listed above – 1966, 1984 and 1995 – were unique for various reasons. The Vietnam war and inflation spike of 1966 cannot be fully compared with the post-Volcker shock Reaganomics of 1984 or the pre-emptive rate hikes of Alan Greenspan’s Fed in 1994/1995.

However, they do share common patterns that can offer insights into the likelihood (or lack thereof) of achieving a similarly favourable outcome for the US economy this time around.

Monetary and fiscal policy: easing comes early

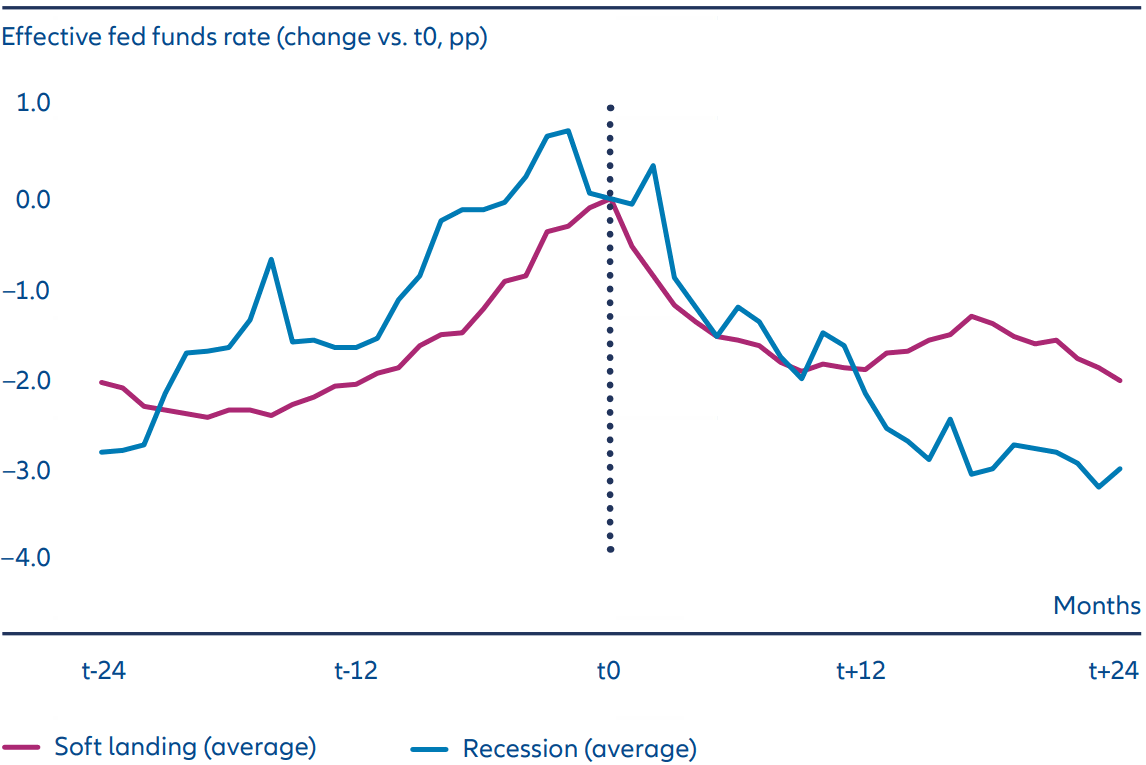

Monetary policy assumed a supportive stance early in all three soft landing episodes, with the Fed cutting interest rates within six months of its “final hike” (see Exhibit 2). This easing was reinforced by decreasing short-term real interest rates and an acceleration in money supply growth. On the fiscal front, however, policy remained rather neutral, as the budget deficit exhibited a broadly sideways movement.

Exhibit 2: In previous soft landings, the Fed cut soon after final hike

Source: AllianzGI Global Economics & Strategy, Bloomberg, data as at 30 September 2023. Recession average based on recessions from 1953-2009. t0 = start of recession and/or final rate hike in respective Fed tightening cycle before a soft landing. Current episode based on the assumption of a final Fed rate hike in Q4/2023.

Supply-side: positive productivity and labour market trends

On the supply side, the economy found support in an improving productivity trend and favourable labour market dynamics, resulting in a moderate acceleration in potential GDP growth. Labour supply received a boost from ongoing healthy growth in the labour force, strengthened by a stable to higher participation rate. Solid employment growth, stable to lower unemployment and a gradual acceleration in wage growth contributed to robust gains in real disposable income throughout these episodes.

Demand-side: private consumption remains robust

From the demand side, this favourable income trend combined with a falling savings rate maintained private consumption at a robust pace. Though sluggish residential investment and dropping business inventories were a drag on economic output, they were partially offset by solid non-residential investment. Positive contributions from government spending further supported the overall economic landscape.

Reflecting on history, successfully navigating the narrow path toward a soft landing required a combination of various policy, supply and demand factors acting in parallel.

Why this time looks different

In comparison, the current backdrop appears significantly more challenging than these previous episodes.

On the policy front, as we approach 2024, monetary policy and increasingly stringent financial conditions are anticipated to pose growing headwinds for economic growth, compounded by a fiscal stance set to turn moderately restrictive. The Fed's 525bp of rate hikes since March 2022 have already been more aggressive than the quantum of hikes put through in 1966 and 1995 (300bp) and in 1984 (325bp), albeit from a much lower starting point. These challenges are heightened by a fragile global economic environment, with Europe on the brink of recession and China experiencing sluggish growth.

While supply side trends have been more encouraging lately, we have doubts about their sustainability. The labour force has continued to rebound from the Covid-related shock, propelled by an uptick in the participation rate. But with the participation of prime-age workers (25-54 years) already high, any further improvement will rely on the (re-)engagement of older workers, which with “baby boomers” approaching retirement and the trend towards early retirement looks unlikely. On a positive note, there has been an uptick in labour productivity over the past year, albeit from rock-bottom levels. While some economists see this as the start of a secular productivity boom driven by new technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI), we think it can still primarily be explained by normal cyclical swings. We are cautious about placing bets on stronger productivity growth as a major catalyst for a soft landing over the next year.

On the demand side, private consumption remains a wildcard amid a resilient yet gradually weakening labour market. Uncertainties linger regarding the amount and impact of residual pandemic excess savings, alongside subdued consumer sentiment. Rising ambiguities in both domestic and global economies, coupled with ongoing margin compression, higher interest rates, and persistent geopolitical risks, are expected to exert pressure on business investment. Elevated interest rates will also weigh on residential investment, and government spending may normalise from recently elevated levels.

The key lesson from the historical comparison is that the necessary adjustments the Fed is targeting for the US economy (a weaker labour market, slower wage growth, lower core inflation) differ from the dynamics of previous soft landing episodes (stable or lower unemployment, steady to higher wage growth, stable core inflation).

Trigger warning: the labour market

However, the historical comparison isn’t the only reason we see a recession as more likely than a soft landing. While forecasting the exact timing and depth of an economic downturn is inherently difficult, numerous indicators suggest the US economy has entered a vulnerable late-cycle stage – most prominently, an ultra-tight labour market, shrinking profit margins, declining money supply growth, and an inverted yield curve.

The lingering risk of structurally higher inflation – not to mention the imperative to restore its credibility as an inflation fighter – means the Fed is unlikely (or arguably unable) to pre-emptively cut rates, even in the face of weaker GDP growth. Policymakers might even find themselves compelled to implement further hikes if the economy resists slowing down adequately or if the disinflation trend stalls prematurely. We see a material risk that the Fed will only discern in hindsight the point when its "higher for longer" stance proves "sufficiently restrictive for long enough”. An overtightening of broader financial conditions could thus serve as the inadvertent trigger for recession.

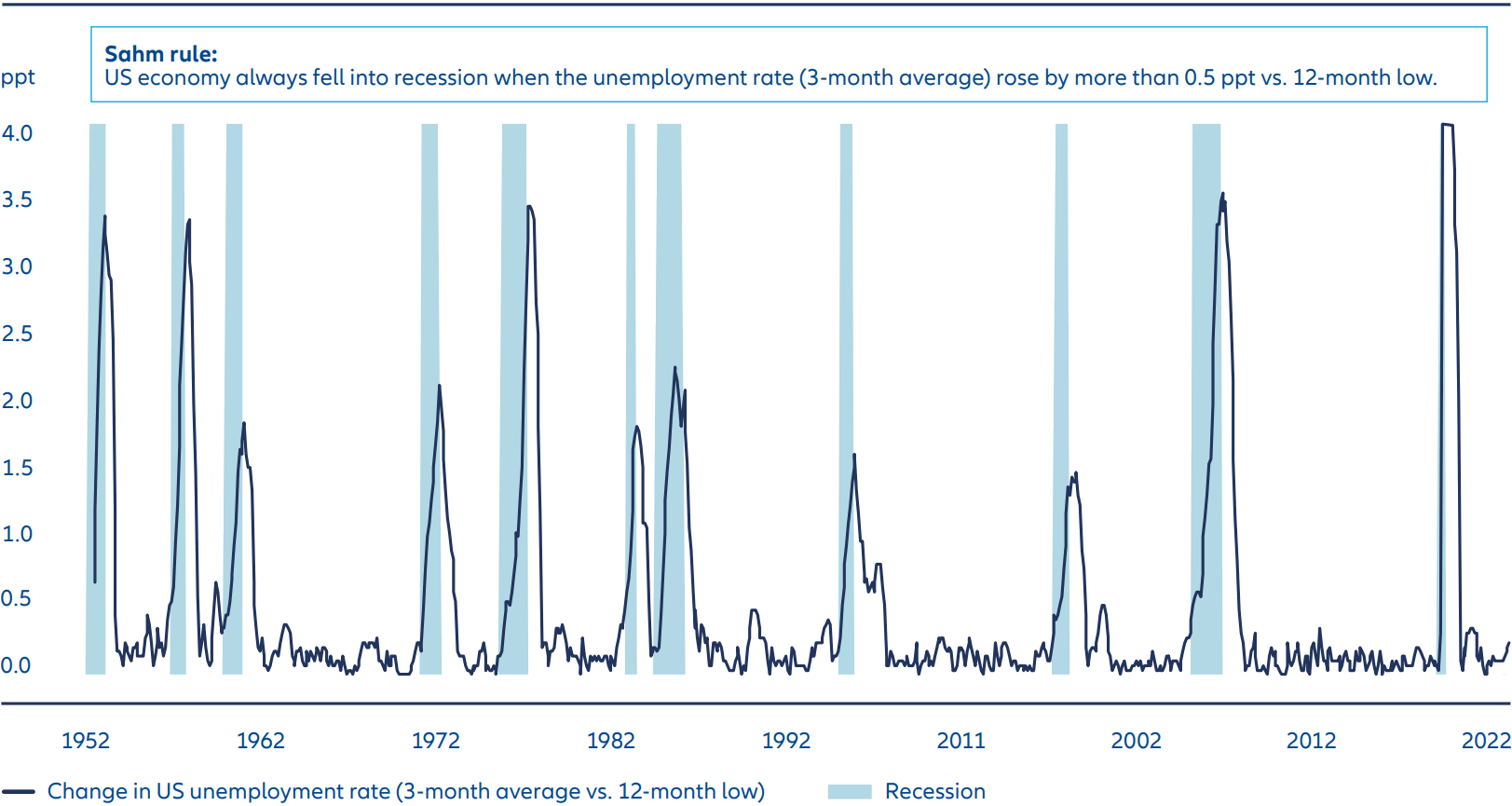

For investors, the labour market could be a valuable indicator of whether the Fed is successfully walking the narrow path to a soft landing. To alleviate cyclical inflation pressures, the Fed aims to slow down economic growth to a below-potential pace for some time and to chill the red-hot labour market. According to the latest median projections from Fed committee members in September, the unemployment rate is expected to rise only moderately from the recent low of 3.4% in 2023 to 4.1% in 2024. But based on historical evidence, even such a subdued deterioration has historically triggered recession (see Exhibit 3).

In any case, we remain skeptical that the Fed can curb inflation without a more substantial weakening of the labour market – ie, one that goes beyond the reduction in still-elevated vacancies and minor increase in unemployment we have seen so far. Barring “immaculate” disinflation, a soft landing of the US economy still appears rather unlikely.

Exhibit 3: Deteriorating labour market has always led the US into recession

Source: Allianz GI Global Economics & Strategy, Bloomberg, data as at 29 September 2023. Sahm rule named after economist and former Fed researcher Claudia Sahm.

Economic cycle more important than monetary policy

Historically, it has been the economic cycle rather than monetary policy that has predominantly influenced risk asset performance. Analysing the past 12 Fed hiking cycles, US equities suffered losses after the final rate hike whenever the economy fell into recession within 12 months (see Exhibit 4). By contrast, equities performed strongly over the following three, six and 12 months whenever there was a soft landing, or when a recession occurred 12 months or more after the final rate hike (a delayed recession).

Exhibit 4: S&P 500 performance following final rate hike

Source: Allianz GI Global Economics & Strategy, Bloomberg, data as at October 2023. Based on analysis of 12 Fed rate hike cycles between 1963 and 2018, classified as either recession, delayed recession or soft landing. Past performance is not an indicator of future results.

Considering the current structural upside risks to inflation, downside risks to the global economy, and the presence of severe geopolitical tensions, along with limited visibility and central banks taking more opportunistic approaches, the investment environment remains exceptionally challenging.